Life in the Mountains

- You started living in the mountains in a different location from where you are now, right?

-

Takanaka (Hereafter, T)

I began living on the slope of another mountain. Honestly, the exact location didn’t matter to me, so I decided on the first place I was shown. There was a small house on about 500 tsubo of land (roughly 1,650 square meters), and I felt it had potential. With such a large plot, I could grow vegetables and support my family. The house itself, however, was in terrible condition. There was a large hole in the roof — you could see the sky through it — so I repaired it little by little while living there.

-

- Was it difficult when you first started living there?

-

T

Yes. The land was teeming with mountain leeches, and everyone — including the children — ended up completely covered in blood. Sometimes, when we went into the city, I felt a deep sense of being home and quietly thought, “Ah, we’re back…” As I wrote in my book 山是山水是水 (‘Yama Kore Yama, Mizu Kore Mizu’, translated as “Mountain is Mountain, Water is Water”), I took everything — including the hardships — as my own responsibility and somehow managed to get through it.

For the children, I think simply living in the mountains was more than enough to be enjoyable. Not just for children — anyone will naturally adapt to their environment. And now, they’ve also adapted to city life. My eldest son, once skilled at slaughtering and butchering chickens, has recently said, “I might not be able to do it anymore, you know.”

-

Regarding creative activities

- How did you get started with pottery?

-

T

I originally started doing day labor to support my family—things like mowing the grass at golf courses or repairing landslide damage. Working at those sites, I handled soil a lot, and gradually I thought, “Maybe I could do pottery with this same feeling of working with the earth.” That’s more or less how I started—just kind of casually, without any particular plan.

-

- Did you learn everything on your own?

-

T

I’ve always had a fondness for antiques—collecting various things and watching films about them—so perhaps I already had a certain grounding. I was also fortunate to have opportunities where people taught me different things. But once you live up in the mountains, inevitably it becomes self-study. Most of the work was the kind you only understood by actually trying. I began when I was 29, so this year makes 30 years.

At one point, the president of the company where I used to work said, “Why don’t you take on some work for us?” and gave me a job distributing flyers. I would deliver a week’s worth to Tokyo, get paid, and save up. With that money, I bought a large amount of scrap materials and began building a kiln.

-

- At that time, there was no internet and very little information available. How did you go about building a kiln?

-

T

I often used to go to the Shoji Hamada Memorial Mashiko Reference Collection and studied the kilns there as carefully as I could. But no matter how closely I looked, once I actually started building one myself, I realized I didn’t understand at all. Somehow I managed to give it shape, but the first kiln collapsed after only six firings.

Through trial and error, the kiln I use now can fire in a relatively short time, so I’ve been able to keep going. But if I had stuck with the old kiln, I don’t think my body could have endured it. Honestly, once I’ve burned through the firewood I have now, I intend to stop making pottery. I’ve already reached sixty, and firing a kiln through the night really is grueling work.

-

- I’d like to ask about your painting as well. You had already been working on painting before you started living in the mountains, right? Does it feel different from pottery?

-

T

Yes, I even held solo exhibitions. Painting is more difficult, you know. Because you have to create everything entirely from zero. With pottery, there’s the texture of the clay itself, the assistance of the wheel, and in the end the fire completes the work. But painting isn’t something just anyone can do.

The biggest difference between pottery and painting is the part of the brain you’re using. Of course, you also use your heart. With pottery too, you use both brain and heart, but because there are repetitive tasks, you can produce a certain volume. Painting isn’t like that. The kind of physical fatigue it brings is completely different as well.

-

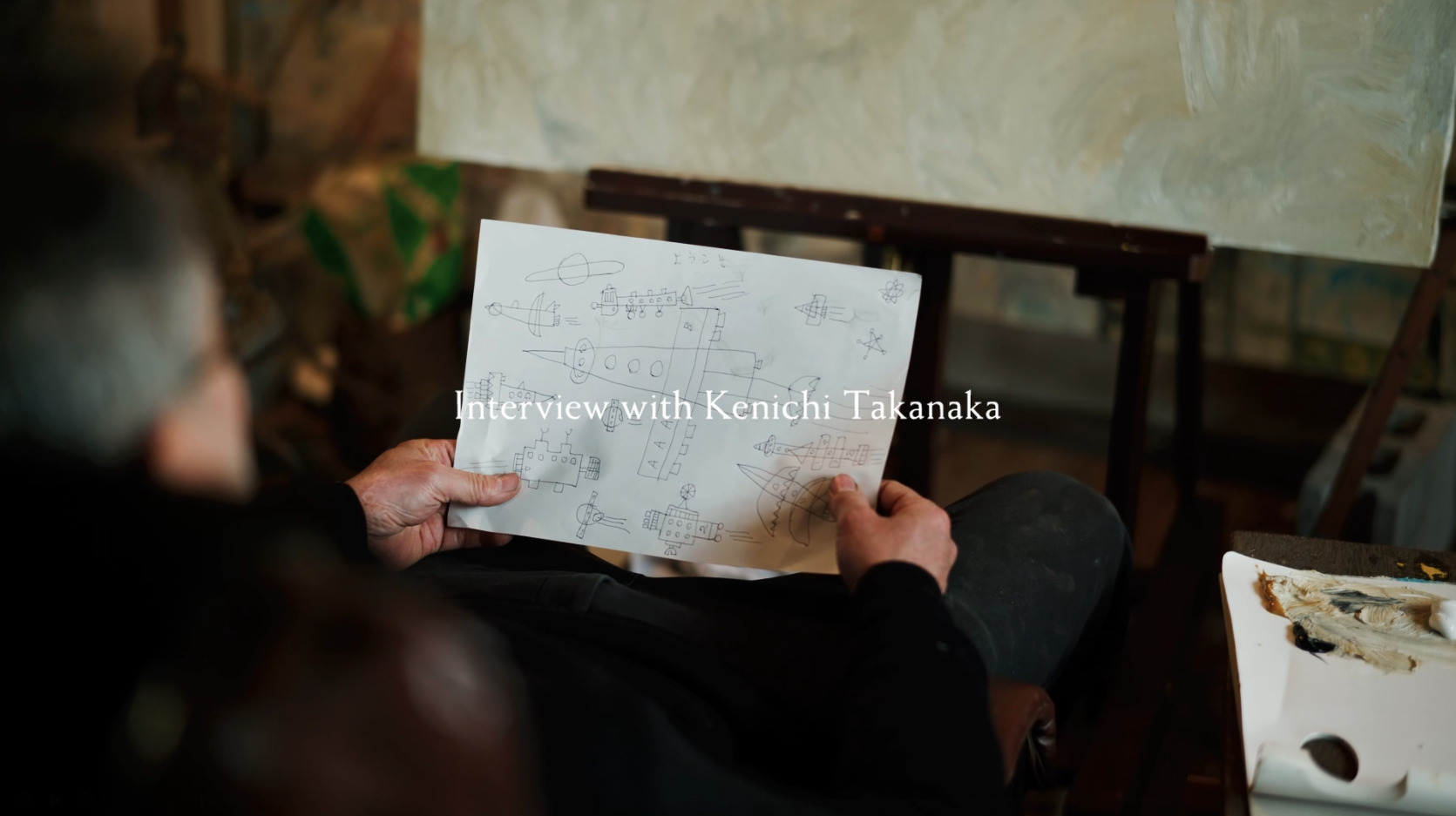

- At first, your series focused on everyday life. After that, it shifted toward ‘Space Defense Force.’ Around this point, one can sense a change in your style. How do you perceive that yourself?

-

T

Even in the early works depicting everyday life, there were major challenges and changes before I arrived at that point. By “everyday,” I don’t mean only the present moment—time from my childhood is also an important part of my everyday. That’s why the kaiju and space I was obsessed with at the time naturally poured out from within me. I suddenly realized, “Ah! This is what I truly like.”

When I actually tried turning that into a work, it was fun. So it wasn’t a sudden change; the appearance of space and kaiju was simply an extension of valuing everyday life. You could say it’s something honest, raw, and emerging directly from my own core.

-

- Your paintings seem to combine the innocence of a child with the perspective of an adult. I feel that expression is remarkable. You’ve said before that achieving that is difficult.

-

T

It’s very difficult. If I try to paint purely like a child, it ends up feeling forced. Inevitably, the “adult” elements I’ve acquired through the process of growing up appear in the work. But I don’t intend to deny that. On the contrary, I try to paint while bringing them along, accepting everything as it is. Right now, I really enjoy engaging with this style.

-

Everyday Life and Zen, and What Lies Ahead

- Could you tell us about a typical day?

-

T

I wake up at 4 a.m., start the fire, and boil water. After breakfast, I go to my study on the second floor, read classical Chinese poetry aloud, and begin work. Then, together with my wife, I go into the mountains with our dog, collecting firewood in a backpack before returning home. After that, I take care of the goats.

From there, it’s time for study in the arbor. Right now I’m studying Japanese classics, so I read The Tale of Genji aloud and practice zazen. Afterward, in the room where I keep the Buddha, I chant the Heart Sutra, then engage in creative work such as oil painting and pottery.

After lunch and a nap, I do physical labor, like splitting firewood. In the evening, I take a bath, enjoy drinks while snacking on my cooking, and always watch one episode of an old tokusatsu show (live-action superhero tv show). Right now, I’m watching Moonlight Mask, which aired before I was born, and I find it educational as well. Then I get into bed and fall asleep while reading a book.

-

- To what extent has Zen influenced you at a fundamental level?

-

T

It’s significant. But if someone asks, “What exactly is the influence of Zen?” it’s very difficult to answer.

-

- You’ve mentioned wanting to eventually stop pottery, but will you continue creating in the future?

-

T

To live is to create. What I’m conscious of is that I want to devote all the remaining energy of my life to making work. I’m not trying to become some extraordinary artist, nor am I aiming for anything in particular. Everything is determined by heaven. Whether my work sells or doesn’t sell, I want to keep creating just the same. I’ve lived that way all my life.

-

PROFILE

Born in 1966 in Toride City, Ibaraki Prefecture, Takanaka left Gakushuin University and began self-studying calligraphy and painting, drawing inspiration from Chinese classics, Buddhist scriptures, and Japanese literature. In 1993, he built his own wood-fired kiln in Otaki, Chiba Prefecture, and embarked on a serious career in ceramics. His works, created while living a semi-self-sufficient lifestyle, are noted for their unique sensibility and expression. He has held solo exhibitions at various galleries, showcasing his distinct artistic vision.

- ARTIST

Kenichi Takanaka