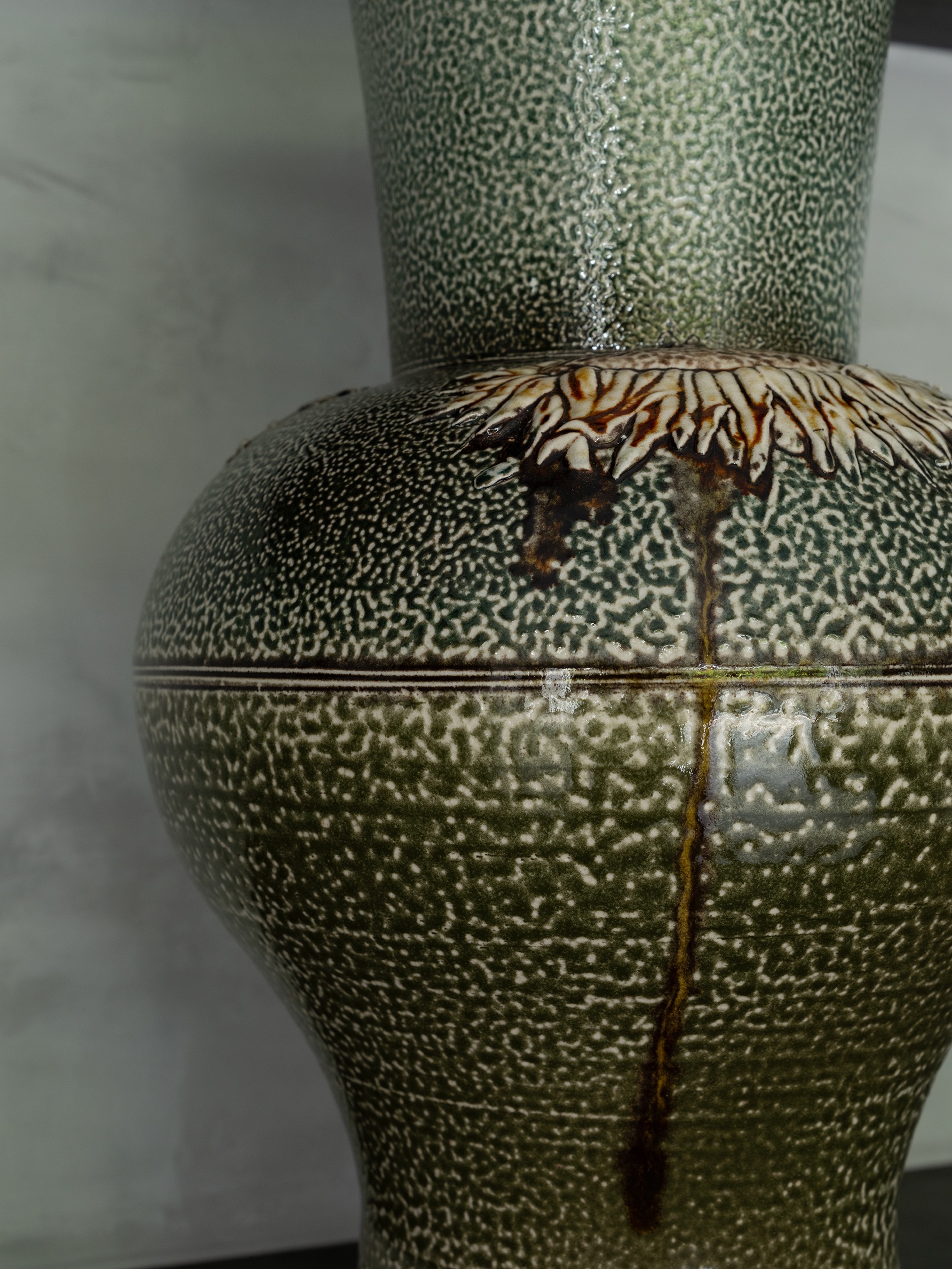

Steve Harrison was born in northern England in 1967. He first encountered ceramics during his high school years and, after graduating from the Royal College of Art (RCA), has continued his practice based in London and Wales. He is best known for salt-glaze firing, a process in which salt is introduced into a high-temperature kiln, producing unpredictable and fluid surfaces. These effects emerge from a rigorous process shaped by factors such as the condition of the kiln, the weather, and even the subtle control of the fire. It is precisely this uncertainty that he finds compelling, refining it into the core of his work.

While his work has earned high acclaim both in Japan and internationally, his focus has consistently remained on who his works ultimately pass into the hands of, and how they are used in daily life. His belief that value is nurtured through everyday use quietly permeates his work.

The Evolution of Form and Thought: The Mug Cup as an Object

- Over the course of your practice, from your early years to the present, what changes and shifts in your thinking have taken place?

-

Steve Harrison (Hereafter, S)

One of the things that has been paramount in how I work, or consistent if you like, is the handle of the mug cup. I’ve always evolved through handles. They began as quite simple strap handles on the body, and then developed alongside the body into different and more complex forms. Being drawn to that complexity felt like a natural progression.

But recently my thinking has started to change. Before, I would look at a handle, see another form, and think, that’s a new mug. Now I’m starting to think that the same handle could be a different mug — it’s just how you think about it. When the handle becomes a device for making a new cup, I don’t really like that. It also made me aware of a habit I might have had before.

What I don’t like is that if you change the handle, then the desire for the mug — even in collection terms — isn’t that strong, because someone might want it simply because they don’t have that handle yet. I don’t want it to be like that. I want it to be something a little bit different.

So now I feel I’d rather concentrate on one handle and see what I can do with that one handle: how it fits, where it goes, the balance, and how those things change. Before — especially early on — you change the handle and it’s a new cup. Great. But now I want to move beyond that.

-

- When do you feel your own distinctive style emerged and took shape?

-

S

When I think about what we call my style, I come back to salt glaze. It’s a European technique, and I find it especially interesting that it has been so well received in Japan. In my early days, I worked through what you might call a fairly textbook approach to glazing and firing, and at that stage I was really asking: what can you actually do with salt glaze?

Salt glaze is extremely difficult to control, and each firing produces its own unique texture and surface. You are constantly faced with the question of whether to accept that unpredictable quality or to resist it. Through a process of trial and error, I gradually began to develop my own approach and take it to a slightly different place.

One example is the combination of materials, such as a stoneware body with a porcelain handle. I’m drawn to the visual contrast, but technically it’s quite challenging. If I’ve done anything with salt glaze, I think it’s been an attempt to take it somewhere else.

-

- Are there any forms or motifs that you have continued to pursue with particular dedication?

-

S

Mug cups. Because I’m obsessed with them. Through using a mug cup, you build a relationship with it, and over time it becomes part of you. For me, nothing is more important than that. Color is something that is constantly changing, so rather than focusing on color, I want to concentrate on the form of the cup. Even just biscuit-firing it would be enough.

Even if this were the very last piece I were to make, what matters to me is not becoming invested in the final outcome, but whether I feel excited by the form that emerges in that moment. Thinking without being bound by glaze or by what happens in the kiln—that is the way I think now, and I feel that it has become my philosophy.

-

The value of continuing to create

- Making ceramics is demanding work. Have you ever thought about stopping?

-

S

Yes, it really is grueling on the body. In my case, it’s not only the making itself but also transporting the work, which makes it even more so. I work in Enfield, in north London, where I make the pieces and carefully wrap everything while it’s still just biscuit-fired, load it into the car, and drive it to Wales. There, I unpack everything, put it into the kiln and fire it, then wrap it all back up again and bring it back to London — and I repeat that process over and over. Looked at objectively, it might seem a bit crazy (laughs).

People around me say, “I don’t know how you keep it going,” and as I’ve gotten older, it’s true — everything feels heavier. It’s certainly not an easy job. I’m 58 now, but even so, I’ve got to try and keep going.

-

- How do you see your creative work developing going forward?

-

S

I might slow down a little. But to be honest, I don’t really know myself. Salt glazing is incredibly seductive. When I’m completely exhausted, I sometimes think, “I can’t do this anymore — I’ve done enough.” But once the firing is finished, somehow I find myself thinking, “I want to do another one.” It’s a problem, really (laughs). It is demanding, but I genuinely love salt glazing.

-

- What does “value” mean to you?

-

S

People experience value differently, don’t they. For example, if we take one of my mug cups, what is its value? At the very least, it’s not about price. The real value lies with the person using it.

If someone is drawn to the mug and wants to use it, they have to accept that it can’t go in the dishwasher and needs to be washed by hand each time. If they can’t accept that, then honestly, I think they’re better off not using my work. That’s simply one reality.

On the other hand, there is also value in placing it in a cabinet and simply looking at it. Just as a still life can move you, finding beauty in an object that way is also a valid form of value.

That said, I believe that by actually using an object in daily life, its value deepens and becomes more personal. It may eventually become something you can’t live without. For me, that is where value truly lies. Something I’ve made becoming indispensable to someone—that is my hope, and that is what value means to me.

-

PROFILE

Steve Harrison is an English potter born in 1967. After obtaining his MA in ceramics at the Royal College of Art, he set up his workshop and his kiln on the outskirts of London, where he now bases his artistic activities. He is known for his mugs and jugs created by the salt glaze technique, which uses common salt for the glaze coating.

- ARTIST

Steve Harrison

Interview photo & video: Kohei Omachi

Event photos (middle of the video): Makoto Ito